I am a 12th great grand daughter of Mary Dyer, the Quaker prophetess, preacher and martyr.

Convinced that the intolerant law of Massachusetts Colony banishing Quakers violated God’s law, Mary Dyer would not stay quiet or stay away. Mary was a Quaker, and Quakers believed that God could communicate directly to us and that salvation could be assured. This was considered heresy by the Puritans in Massachusetts, so they banished her from the colony. She was brought before the Court of Magistrates, which sentenced her to death and publicly hanged on June 1, 1660.

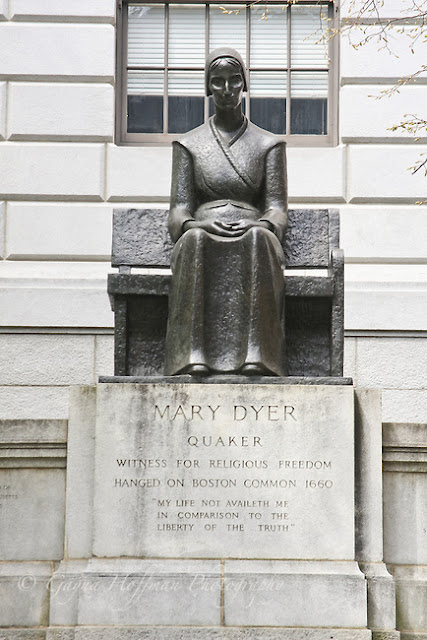

Mary Dyer (born Marie Barrett; c. 1611 – 1 June 1660) was an English and colonial American Puritan turned Quaker who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony. She is one of the four executed Quakers known as the Boston martyrs.

While the place of her birth is not known, she was married in London in 1633 to the milliner William Dyer. Mary and William were Puritans who were interested in reforming the Anglican Church from within, without separating from it. As the English king increased pressure on the Puritans, they left England by the thousands to go to New England in the early 1630s. Mary and William arrived in Boston by 1635, joining the Boston Church in December of that year. Like most members of Boston's church, they soon became involved in the Antinomian Controversy, a theological crisis lasting from 1636 to 1638. Mary and William were strong advocates of Anne Hutchinson and John Wheelwright in the controversy, and as a result Mary's husband was disenfranchised and disarmed for supporting these "heretics" and also for harboring his own heretical views. Subsequently, they left Massachusetts with many others to establish a new colony on Aquidneck Island (later Rhode Island) in Narraganset Bay.

Before leaving Boston, Mary had given birth to a severely deformed infant that was stillborn. Because of the theological implications of such a birth, the baby was buried secretly. When the Massachusetts authorities learned of this birth, the ordeal became public, and in the minds of the colony's ministers and magistrates, the monstrous birth was clearly a result of Mary's "monstrous" religious opinions. More than a decade later, in late 1651, Mary Dyer boarded a ship for England, and stayed there for over five years, becoming an avid follower of the Quaker religion that had been established by George Fox several years earlier. Because Quakers were considered among the most heinous of heretics by the Puritans, Massachusetts enacted several laws against them. When Dyer returned to Boston from England, she was immediately imprisoned, and then banished. Defying her order of banishment, she was again banished, this time upon pain of death. Deciding that she would die as a martyr if the anti-Quaker laws were not repealed, Dyer once again returned to Boston and was sent to the gallows in 1659, having the rope around her neck when a reprieve was announced. Not accepting the reprieve, she again returned to Boston the following year, and was then hanged to become the third of four Quaker martyrs.

Dyer returned to Boston on 21 May 1660 and ten days later she was once again brought before the governor. The exchange of words between Dyer and Governor Endicott was recorded as follows:

Endicott: Are you the same Mary Dyer that was here before?

Dyer: I am the same Mary Dyer that was here the last General Court.

Endicott: You will own yourself a Quaker, will you not?

Dyer: I own myself to be reproachfully so called.

Endicott: Sentence was passed upon you the last General Court; and now likewise--You must return to the prison, and there remain till to-morrow at nine o'clock; then thence you must go to the gallows and there be hanged till you are dead.

Dyer: This is no more than what thou saidst before.

Endicott: But now it is to be executed. Therefore prepare yourself to-morrow at nine o'clock.

Dyer: I came in obedience to the will of God the last General Court, desiring you to repeal your unrighteous laws of banishment on pain of death; and that same is my work now, and earnest request, although I told you that if you refused to repeal them, the Lord would send others of his servants to witness against them.

Following this exchange, the governor asked if she was a prophetess, and she answered that she spoke the words that the Lord spoke to her. When she began to speak again, the governor called, "Away with her! Away with her!" She was returned to jail. Though her husband had written a letter to Endicott requesting his wife's freedom, another reprieve was not granted.

On 1 June 1660, at nine in the morning, Mary Dyer once again departed the jail and was escorted to the gallows. Once she was on the ladder under the elm tree she was given the opportunity to save her life. Her response was, "Nay, I cannot; for in obedience to the will of the Lord God I came, and in his will I abide faithful to the death." The military commander, Captain John Webb, recited the charges against her and said she "was guilty of her own blood." Dyer's response was:

Nay, I came to keep bloodguiltiness from you, desiring you to repeal the unrighteous and unjust law of banishment upon pain of death, made against the innocent servants of the Lord, therefore my blood will be required at your hands who willfully do it; but for those that do is in the simplicity of their hearts, I do desire the Lord to forgive them. I came to do the will of my Father, and in obedience to his will I stand even to the death.Her former pastor, John Wilson, urged her to repent and to not be "so deluded and carried away by the deceit of the devil." To this she answered, "Nay, man, I am not now to repent." Asked if she would have the elders pray for her, she replied, "I know never an Elder here." Another short exchange followed, and then, in the words of her biographer, Horatio Rogers, "she was swung off, and the crown of martyrdom descended upon her head.

— Dyer's words as she prepared to hang

No comments:

Post a Comment